The Baha’i Faith starts with the premise that there is only one God, all religions have come from the same Source, and all have the same spiritual Truths. - As with Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the Baha’i Faith is Abrahamic in origin, tracing from Abraham’s first and third wives, Sarah and Keturah. The Baha’i Faith is the most recent in series of religions, and will be followed by others as humankind continues to mature spiritually.

In the mid-1800s, scholars of many faiths were expecting the appearance of the Promised One. In particular, some Christians were expecting the return of Christ, and Muslims the Qa’im or the Mahdi. In 1844 in Persia (now Iran), society was undergoing a moral breakdown. When a young man named Ali-Muhammad announced that He was the bearer of a new Revelation from God, tens of thousands of people responded to His call. His title was “The Báb” (The Gate). Although He had very little formal schooling, He was widely known for His wisdom and integrity in life and business. The Bab‘s mission lasted only six years (1844-1850). In those six years He received voluminous Revelation from God, and the new teachings spread rapidly all over Persia. His followers were called “Bábis” (followers of The Bab). He made clear that the most important part of His mission was to prepare the way for the coming of another Manifestation or Messenger of God, Who would usher in the age of peace and justice promised in all the world’s religions: Bahá’u’lláh. Bahá’u’lláh (“The Glory of God”) was born to a noble family in Tehran. His given name was Mirza Husayn-Ali, and He had all the accoutrements and privileges one would expect of nobility. His father served as a minister in the court of the Shah, and it was widely accepted that the son would follow in His father’s footsteps. But once He heard the message of The Bab, His path took another turn.

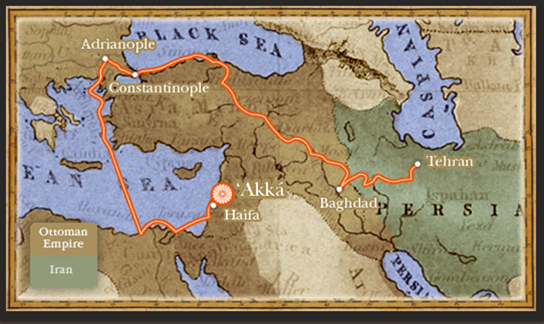

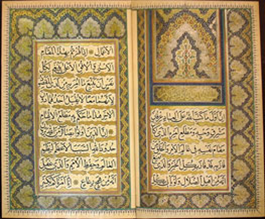

On July 9, 1850 The Báb was put to death by rulers who feared His influence. Bahá’u’lláh assumed leadership of the young Faith. Being known as a Bábi was dangerous, and after a few years Bahá’u’lláh was imprisoned for a crime He did not commit. Upon His release (1853) He and His family were exiled to Baghdad, from where the Shah hoped His influence in Persia would die out. For ten years Baha’u’llah and His family and followers lived in Baghdad. While residing in Baghdad, Bahá’u’lláh composed three of His most renowned works at this time—the Hidden Words, the Seven Valleys and the Book of Certitude (Kitáb-i-Íqán). These writings alluded to His station, but it was not yet the time for a public announcement.

When it was clear His influence was growing, another exile was ordered. It was on the eve of that move, in April 1863 over a twelve-day period, when Bahá’u’lláh announced to His closest family, friends and followers that He was the Promised One foretold by The Báb. During the ten years in Baghdad, Bahá’u’lláh had become well known and loved, and thousands of ardent supporters visited to lament His leaving. These twelve days are celebrated now as the Festival of Ridvan (Paradise), the holiest time of the Baha’i year.

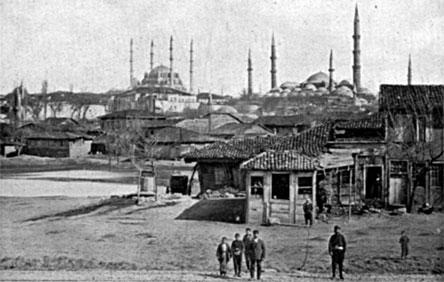

The exiles - now known as Bahá’is, or followers of Bahá’u’lláh - arrived in Constantinople (now Istanbul) a few months later, only to be further exiled to Adrianople (Edirne), where they stayed until about 1868. And still His influence was felt in Persia. A final exile was ordered. After 15 years of being sent further and further from their home, the exiles landed in the prison city of Akka (Acre), Palestine, in August 1868. The city was so filthy and vile that they were not expected to survive.

A Prisoner in or near Akka for the remainder of His life, Baha’u’llah gradually gained a little more freedom to move about the area over time. But in the first two years, when believers walked for three months from Persia to see Him, the closest they could get was across a moat. From there they could see His cell window, and hope to see Him wave a kerchief out the window acknowledging their presence.

Confined to a prison for more than two years, He and His companions were later moved to a cramped house within the city's walls. Little by little, the moral character of the Bahá’ís—particularly Bahá’u’lláh’s eldest son, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, softened the hearts of their jailers and won over the residents of the city. As in Baghdad and Adrianople, the nobility of Bahá’u’lláh’s character gradually won the admiration of the community at large, including some of its leaders.

In ‘Akká, Bahá’u’lláh revealed His most important work, the Kitáb-i-Aqdas (the Most Holy Book), in which He outlined the essential laws and principles of His Faith, and established the foundations for a global administrative order.

In the late 1870s, Bahá’u’lláh—while still a prisoner—was granted some freedom to move outside of the city's walls, allowing His followers to meet with Him in relative peace.

(Photo of Mazra’ih, Bahji) In April 1890, Professor Edward Granville Browne of Cambridge University met Bahá’u’lláh at the Mansion of Mazra’ih, one of the places Bahá’u’lláh lived as the restrictions eased. Browne wrote of their meeting: “The face of Him on Whom I gazed I can never forget, though I cannot describe it. Those piercing eyes seemed to read one's very soul; power and authority sat on that ample brow…No need to ask in whose presence I stood, as I bowed myself before one who is the object of a devotion and love which kings might envy and emperors sigh for in vain.”

The Covenant of Baha’u’llah Bahá’u’lláh passed away on 29 May, 1892. In His will, He designated His eldest son ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as His successor and Head of the Bahá’í Faith — the first time in history that the Founder of a world religion had named His successor in a written irrefutable text. This choice of a successor is a central provision of what is known as the “Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh,” enabling the Bahá’í community to remain united for all time.